For ease in writing the author refers to the perpetrator as ‘he’ and the victim as ‘she’. Of course research is clear that violence within intimate relationships can occur between all genders, all ages, in heterosexual and same-sex relationships, with both male and female perpetrators to male and female victims as adults and as children. It is an interesting exercise to change the genders around when reading this guide to challenge thinking and possible misperceptions.

aaaVisual composer – practice guidance test (A trauma model in domestic abuse situations)

Introduction

Using a trauma model (Ross, 2000) to work with those experiencing or perpetrating domestic abuse enables social workers to understand:

- Why, and how, people who experienced domestic violence in their home as a child are attracted to, and are attractive to, each other in adulthood.

- Why after a break up from a violent partner and living alone or in a refuge, a victim may, within months, find themselves in another violent relationship.

Violence experienced in childhood extends beyond just physical violence. It includes any form of violence, including emotional neglect, that is experienced within a relationship that should have been safe and nurturing. A trauma model is particularly useful in assessing any child protection concerns.

There are four concepts that underpin a trauma model which inform social work interventions, assessments and therapy. These are:

- No blame.

- No shame.

- Empathic curiosity which enables both the client and social worker to remain with their “window of tolerance”.

- The client’s behaviour is not the problem, but the answer to the problem.

These concepts allow the social worker to explore the reasons why there is an attraction to a violent partner, an attraction to a potential victim and the implications for the couple, as individuals/parents, and their children, not only in the present but for future generations.

What is meant by no blame, no shame and empathic curiosity?

It is not unusual for victims of domestic abuse to describe feelings of deep shame and/or self-blame (Perry et al, 1996) when:

- They express a reluctance or inability to leave especially when the consequences of staying are so serious (for example, further injury to themselves or their children or the children being removed into care).

- They believed the partner’s promise it will not happen again, and then it does.

- Having tried, they did not succeed in leaving for the first, second, third (and so on) time. Each additional failure adds to their sense of shame. This shame often transforms into angry rejection of advice when they experience this as being ‘told off’. It becomes necessary to distance themselves from friends, family and professionals to avoid being told off, and sometimes leads to a greater determination to make the relationship work in order to avoid another “I told you so”.

- Against all advice from friends and professionals, she has been persuaded home again.

- In missing the perpetrator, she contacted him and agreed to meet.

- She has been told many times it was not her fault by friends, family and professionals when she knows or believes it was her fault.

- Having extracted herself from one violent relationship she is then blamed for not learning the expected lessons of how to avoid getting into another violent relationship.

It is therefore very important that any work done with the victim or perpetrator does not reinforce these feelings. Empathic curiosity reduces the likelihood of shame or blame occurring in both client and social worker (Wilson and Lindy, 1994).

It is worth thinking about how many blaming and shaming questions are asked of a victim which begin with the word ‘why’:

- Why didn’t you leave?

- Why did you stay?

- Why didn’t you see this coming, given your experience?

- Why didn’t you tell someone?

- Why did you press his buttons?

- Why didn’t you use the strategies you learned on your Women’s Aid course?

- Why did you tell the police to remove the panic button?

Many ‘shame and blame’ questions all beginning with ‘why’ will inevitably evoke the same answers: ‘I don’t know’ or ‘I don’t remember’.

From a trauma model perspective, these are acknowledged as truthful answers from her point of view. She really doesn’t know the answer and can’t explain why. Her psychological wellbeing is maintained by her not knowing or not remembering (Putnam, 1997; Weiland, 2011; Silberg, 2013). In other words, what she is doing is actively not knowing or not remembering. To know or remember would be too emotionally painful and involve a level of joined-up thinking or evoke memories of the other traumas in her life (Terr, 1997).

Rather than ask ‘why’, it is much more effective and more empathic to start with the word ‘what’ or use the acronym:

This will assist you to explore the reason(s) behind, for example, their initial attraction to each other or what stops her leaving.

| Blaming or shaming | Using TED |

|---|---|

| Why did you fall for him in the first place? | Tell me what it was about him that made you fall for him. |

| Why will you not leave? |

|

To be effective, these open questions must be asked with empathic curiosity. The social worker will then not only obtain more information, but the victim will experience a level of empathic understanding which will enable her, with the emotional support this contains, to be just a little curious about the dynamics within the violent relationship. She might also begin to think, even if just for a moment, that perhaps what causes the violence to happen is not one-sided. Empathic curiosity also keeps both her and the social worker in their ‘window of tolerance’ which should increase the likelihood of her making, and sustaining, necessary changes; and the social worker avoiding empathic strain and burnout (Siegel, 1999, 2012).

What does ‘window of tolerance’ mean?

Siegel (2002, 2012) explains the ‘window of tolerance’ as an ability to tolerate potential stress of any situation. While ‘in the window’ stress is tolerated and managed, for example, high levels of excitement, fear or sadness are managed ‘in the window’. Intolerable distress, however, is ‘out of the window’ and results in one of two possible strategies: i) hypo/shutting down or ii) hyper/frantic responses sometimes swinging between the two mimicking the diagnostic criteria for ADD (attention deficit disorder)/ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) or depression, bi-polar or borderline personality disorder.

For more information see Inform’s guide to Understanding a child’s neurobiology to assess the impact of contact with birth parents.

The victim’s one-sided view about whose fault it is, is one which must be explored without shame or blame. It is easy for those working with victims to want to reassure the victim who says ‘it is my fault this happens’ by replying ‘I’m sure it was not your fault’. The necessity of self-blame must be kept in mind. Self-blame can enable the victim to have a sense of some control. She knows she has no control over if the harm will happen but she knows she at least has some control over when the harm occurs (Briere, 1992; Sapolsky, 2004; Fonagy et al, 2004).

The issue of control is very often only attributed to the perpetrator but this prevents the social worker from exploring the victim’s behaviour which affirms her belief that she has some control. It is better to ask: ‘What makes you believe this is your fault?’; ‘Tell me when you first thought it was your fault’; ‘Was there ever a time when you thought it was not your fault?’; ‘Describe to me a time when someone told you this was your fault’ (Lipton, 2005).

When the questions are phrased in this way, it is not unusual for the victim to say that she knew from the perpetrator’s mood or movement that there would be an episode of violence and it was her lack of skill, poor timing or inadequate responses that led to the violence. If she could just get these things right, if she could just follow his instructions, there would be no violence.

Feeling as if she is getting things right gives her a sense of control over her partner’s behaviour. Because of this reasoning, she finds it easy to believe her partner when he says she is responsible. She needs to believe this in order to stay safe. Telling her she is not responsible fills her with fear, if not terror, and does not enable her to feel safe enough to consider whether she might be responsible or not. In effect this takes her out of her ‘window of tolerance’ making it impossible for her to tolerate what you say and she will therefore reject it, and you.

Case example: Joanne

Joanne described her partner’s violence towards her as entirely her own fault. When asked to describe a time when she knew this to be true she described knowing the moment her partner came home from work whether or not she was going to get a ‘hammering’. She would ‘tiptoe’ around him until their young children were in bed. She would then ‘press his buttons’ to provoke him to get it over with. She could then have a bath and watch EastEnders in peace without him spoiling her enjoyment of the storyline.

She knew by doing this she controlled his violence. It was her fault she liked EastEnders, it was her fault she provoked him, it was her fault she knew when to shut up and didn’t, it was her fault she could not wait, it was her fault she could not soothe him after a hard day at work.

She waited until the children were in bed before she made it happen. She knew there were times he said he was going to the pub and she stopped him, it was her fault she made him cross which resulted in him drinking and having affairs.

Her partner uses many of Joanne’s beliefs to reinforce to both himself and her that it is her fault he behaves as he does.

A no blame, no shame conversation with empathic curiosity enabled Joanne to understand that in order to stay safe, to keep her children safe and be in control, even just a little, of when the predicted violence happened, she would do something to provoke her partner. She also believed her partner when he said it was her fault and she was responsible for his actions. She knew she could have waited until he chose the moment but this feeling ignited a memory of the terror she felt as a child when waiting for her father to come home from work and then waiting for something to happen.

Making it happen, and being in control of when it happened as an adult managed her terror in the present and from her childhood.

This example can also explain the confusion children can feel about whose fault it is that dad hit mum. A child, like Joanne in the example, is able to recognise the predictive signs of impending violence and knows from experience what behaviours will increase or reduce its likelihood. The child sees his mother behave in a way which will definitely lead to violence. His anger is then directed towards his mother, not his father.

Siding with his father and joining him in blaming his mother then makes sense to him, which at the same time reduces the likelihood of him also being hurt. Yet at the same time he also feels sorry for his mother but is angry with her for telling him it did not happen or it doesn’t matter or it didn’t hurt. The child’s confusion makes him angrier with his mother because he knows his father has made this promise before and again she believed him.

The child’s thought processes adds further confusion about what they should do: which parent should the child ally with – victim or perpetrator? As the child views it, the victim made this happen therefore the perpetrator is the victim but the perpetrator hurt the victim?

Working this out and having, or retaining, any empathy for either parent is too difficult and therefore empathy is dismissed as not useful. The confusion about which parent should have his loyalty or empathy is too much for him to bear. No empathy is much easier to live with. Within the family relationships, the child’s only experience of a model of care is one that serves to ‘meet your own needs first’. He therefore adopts this model to reduce his distress and capacity for empathy.

The child has also worked out that it is not safe to be angry with his father. Further, he sees his mother make relationships with, therefore must love, men who are violent. The child therefore believes his mother will love him too if he is violent towards her. He cannot be empathic towards his mother’s feelings. The child cannot work out what his mother wants and this feeling of helplessness is managed by being angry with her. Anger is something he knows about. The neurobiological changes he experiences in expressing his anger makes him feel better: certainly better than he feels when trying to figure out what is going on (van der Kolk, 1996; Swaab, 2014).

Add to this how much more painful or emotionally distressing it is to bother at all. Surely, it’s much ‘easier’ for the child not to be empathic at all. The child decides to replicate what it appears to him both his parents do – to take care of your own needs first without concern for anyone else who might be impacted by what you do or think. It is this decision, however, that will lead to short- and long-term consequences for behaviours within their current and future relationships (James, 1994).

He has also learned that a high level of attunement without any empathy ensures both physical and, more importantly, psychological survival but the chances of him making safe, positive relationships of emotional depth are significantly impaired (Rich, 2006).

The ‘jigsaw’ metaphor is particularly useful here in explaining and demonstrating how these beliefs and behaviours impact on the next generation and beyond. See also the case example of Jamie below.

The jigsaw metaphor – case study

This jigsaw metaphor was developed in a therapy session in which a therapist drew the two top jigsaw shapes to explain to a 12-year-old girl why her parents decided to stay together despite the mother being told that her partner, the girl’s father, had made their daughter pregnant. The child immediately understood that these represented her parents, her father on the left who never said sorry, always blamed others for his shortcomings, and caused her sexual harm. He lived with her mother who had been harmed and dented by her parents and therefore they fitted together.

This jigsaw metaphor was developed in a therapy session in which a therapist drew the two top jigsaw shapes to explain to a 12-year-old girl why her parents decided to stay together despite the mother being told that her partner, the girl’s father, had made their daughter pregnant. The child immediately understood that these represented her parents, her father on the left who never said sorry, always blamed others for his shortcomings, and caused her sexual harm. He lived with her mother who had been harmed and dented by her parents and therefore they fitted together.

The child and her therapist worked out that because her father (the jigsaw shape on the left) had also been hurt he would need a dent as well as a bump. She then drew the rest of the family as having one dent and one bump. A memory from her science class that ‘matter can neither be created nor destroyed’ led to her realising and accepting that dents on one side of the rectangle lead to bumps on the other. She drew the third row to represent the multiple dents and bumps caused by many harmful incidents and emotional hurts.

In other words the hurt child becomes a parent with this ‘jigsaw’ shape. The child grows into an adult able to make ‘attachments’ to someone who is the same shape so is attracted to another adult with a similar shape caused by their experiences. Their behaviours and attachment style create a child with the same shape. Changing shape requires being able to reflect on not just the harm done and the person who did it, but also what was missing or not done (Freyd, 1996).

The child drew the last two shapes to indicate her foster carer and herself. She then asked, “When does this therapy thing start, because I need to get myself straightened out. If I don’t I’ll stay the same as my parents and my children will be hurt as I was. I’m not having that, so when does it start?”

For more information see Inform’s guide to A trauma model for planning, assessing and reviewing contact for looked-after children.

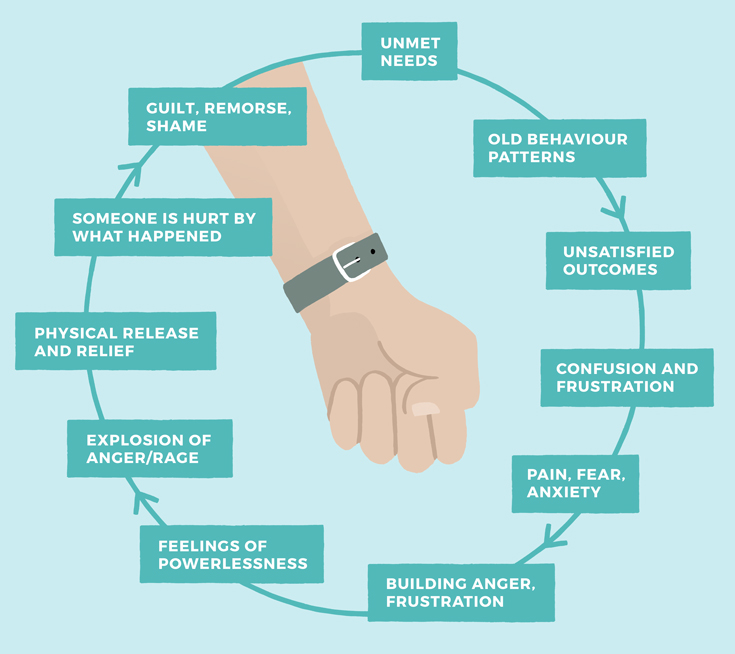

The addiction cycle: exercise

This exercise has been adapted from the Addiction Cycle by Kaufman and Zigler (1987).

The exercise is worth doing based on your knowledge of a situation you are working with. It can then be done with both the victim, perpetrator and the children in the family to help both them, and you, make sense of what is happening as well as identifying the ‘thinking errors’ or coping strategies which keep the family together. It can be a very powerful exercise to do leading to painful realisations of the harm the violence has or is causing or indeed denial of responsibility and angry withdrawal.

You will need:

- a large sheet of paper,

- a pen and

- some post-it notes.

The post-it notes enable jumbled or out-of-order recall to be replaced and put in order where writing on the paper makes this impossible. It is not unusual for recall of traumatic episodes to be out of order, the disorder validates how traumatic the event was (Steller and Koehnken, 1989; Hale, 2009).

Draw a circle on the sheet of paper. Write on a post-it note the words your client uses to describe a period of calm in the household, for example, ok, all well, quiet, safe and place this at the ’12 o’clock’ slot.

On another post-it note write the words used to describe an episode of violence, placing this in the ‘8 o’clock’ slot.

The idea is that once this has been completed, a behaviour cycle and its consequences can be discussed with empathic curiosity, without shaming or blaming the victim or perpetrator. The brain reorganises recall of a traumatic event, especially of a type 2 trauma (see explanation below), to reduce and manage what would otherwise be overwhelming distress with potentially life-changing consequences (Steller and Koehnken, 1989) within the section between 8 o’clock and 12 o’clock clockwise. The excuses, explanations, self-blame, forgiveness and other coping strategies are then included in a modified account of the incident if it is recalled from beginning to end.

For this reason it is useful, by challenging the modified account, and therefore potentially more challenging for client and social worker, to work backwards (anticlockwise) from the event at ‘8 o’clock’ to ’12 o’clock’ using the words ‘and just before that, what was happening?’

As with any individual work being done with a child or an adult, it is important the social worker modulates their own, as well as the client’s, distress to ensure both stay in their ‘window of tolerance’ and are not hijacked by emotional distress ‘out of the window’ into a ‘seven-F response’ (see explanation below) (van der Kolk, 1996; Ogden et al, 2006; Siegel, 2012).

Write on different post-it notes (as many as are needed) the behaviours which lead up to the violence, going backwards, placing these between ‘8 and 12 o’clock’ (anticlockwise) and then the behaviours/thoughts/feelings which enabled the victim to feel ok again placing these post-its between ‘8 and 12 o’clock’ (clockwise). As new information is added or new insights obtained the post-it notes can be moved around. The insights gained from doing this exercise can be very emotionally challenging and painful, for example, what was believed to be an ‘accident’ can now clearly be seen as being planned or part of a pattern.

Example

Type 2 trauma

Type 2 trauma: this is an event or events which are planned and repeated and cannot therefore be described as accidental. There is an overwhelming feeling of fault or self-blame with often disproportionate levels of shame. Shame is differentiated from guilt by the level of self-blame felt, that is, with guilt the belief that it was an awful, disgusting event, with shame, it is me who is awful and disgusting. Type 2 trauma includes all forms of child abuse and interpersonal violence. Harm, within a relationship, leads to the need to absolve the perpetrator from blame which increases the level of self-blame and by doing so enables the attachment and dependency needs of the victim to not be compromised (Herman, 1997).

For more information see Inform’s guide to Understanding a child’s neurobiology to assess the impact of contact with birth parents.

The ‘F’ responses

Increased levels of any physical or emotional feelings cause the neo-cortex (initially necessary to solve a problem) to go off line. The sub-cortex then comes on line and when still no solution is found the limbic system operates with feelings, scripts, internal working models or state dependent memories of other times and places when the same range of feelings were present and the solutions that worked then. The body responds now to these feelings from then, as it did then activating one or more of the seven “F”s on a sliding scale from a little to maximum activity but always the correct amount to ensure physical and emotional survival. The seven “F”s are:

- A flight response, with fidgeting feet, legs and/or fingers into actual running away or daydreaming or dissociating when physical escape is not possible.

- A fight response with clenched fists, tight shoulders, chin out, increased level of breathing and determined thoughts such as “I will solve this problem, it will not get the better of me”.

- A feed response as the stomach tries to produce the necessary energy to enable the other “F”s, often seen as hand placed over stomach, looking sick, tight throat, shallow breathing and thoughts or statements such as “I have butterflies in my stomach”, “I have a gut reaction to this”.

- A “fuck” sexual response with hand over genital area, crossed legs, squirming, need for the loo, flushed skin. For victims of sexual assault this can be very shaming and confusing. It can also be manipulated by the perpetrator to persuade or infer the child is ready for or wanting the sex. This link between high levels of physical or emotional arousal is also seen in violent situations such as domestic abuse and war. Perhaps this can be explained as necessary for the survival of the human race in that if fear and violence inhibited sexual behaviour the human race would have died out in cavemen times or later in times of war and conflict.

- A freeze response is seen with rigid muscle tone, eyes wide, shallow slow breath – no thoughts or words, speechless with terror, unable to understand language, hyper alert to tone of voice, immobilised defences. Later a significant level of self-blame is felt and expressed when there is no understanding that shouting out or screaming was impossible because Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas are “switched off” when in this state of freeze. Tone of voice is a much more reliable indicator of intent rather than the words being used (Perry et al, 1995).

- A flop response with muscles relaxed not tense as in “freeze”, often with the accompanying words “I was never any good, it’s my fault this happened”. This is the body’s way of protecting itself from both physical and emotional injury, indeed ensure survival.

- A fart response is noticed with actual farting or a need to rush to the toilet. This sphincteric response to fear is noted in statements such as “scare the shit out of someone”, being “shit scared”.

For more information see Inform’s guide to Understanding a child’s neurobiology to assess the impact of contact with birth parents.

What is the difference between empathy and attunement and sentimentality?

Empathy is crucial in any work with victims and perpetrators.

Empathy and attunement have many behaviours in common, distinguishing empathy from attunement and sentimentality is vital. My own understanding of the difference came from a conversation with a young adult whose father was serving a long prison sentence for several sexual and violent offences against her, her siblings and her mother. We were talking about her relationship with her father which led to her comment about how much she missed him. When asked what she missed, she described him as ‘the most empathic person I have ever known’. Telling me he was always there for her, always noticing and understanding how she was feeling and always, always being able to alter her mood.

On reflection, what she described as empathy was indeed attunement – an ability to get inside someone’s head, note their feelings, wishes and needs and then, unlike empathy, use this knowledge against them. In this instance, the father used this knowledge to manipulate and cajole her into meeting his needs by exploiting hers. Had he been using empathy he would have attuned to her mood and used this information to meet her needs, not his own.

Sentimentality is an over-emotional response to questions asked but does not lead to changes in behaviour. For example, the parent who cries with distress when asked what impact the violence has had on their children may start to describe how awful it is but in the next sentence turns the attention on themselves – describing their pain and sleepless fear-filled nights.

To further understand the difference between empathy and attunement, it is useful to note that babies are born with an innate ability to attune, which is necessary for their survival (Schore, 2003). Hormonal changes in the mother in the last trimester of pregnancy and after the baby’s birth alters her brain functioning to increase her capacities for attunement and in doing so mother and baby’s brains work together to ensure the baby’s survival (Swab, 2014).

Empathy is learned through an empathic relationship with another. Purposeful age-appropriate misattunement by the mother or main carer, allows the developing baby/child to experience an appropriate level of distress which temporarily removes their feeling of connectedness (with the caregiver). The empathically attuned parent judges how much distress is required ‘appropriate to the crime committed’ and then responds to the child’s growing distress by reconnecting, which lets the child know that their behaviour was not ok but despite that, the child is still loved.

The empathically attuned mother will ensure the baby/child remains within their ‘window of tolerance’. Experiencing an appropriate level of empathic misattunement allows the baby’s ‘window of tolerance’ to widen and increases their understanding of empathy.

The child learns:

- that behaviour has consequences which can cause himself distress;

- that his behaviour can upset other people;

- that mistakes are forgiven.

As a result, a healthy, valued sense of oneself can develop with an ability to be empathic.

This ‘reconnection’ must happen while the child is still in their ‘window of tolerance’. As the distress builds, cortisol is released into the child’s body in preparation for flight or fight to escape the cause of their distress. At the same time the functioning of the child’s Brocas’ and Wernicke’s areas of the brain reduces, which lessens the child’s ability to understand or express words. He is in effect becoming speechless with terror. In this instance a child only pays attention to the tone and texture of what is being said, the actual words are irrelevant. Any explanation given for the purpose of the distress caused by his mother cannot be heard, nor can he explain his behaviour unless he is ‘in his window’ (Siegel, 2012).

Case example: A mother and child

In an interview with a mother – living in a refuge – about her child’s aggressive behaviour towards other children, she was asked what techniques she used to control/punish him. Her response was that she had watched Supernanny and knew about using the naughty step for the number of minutes equal to the child’s years. She therefore sat her child on the naughty step for four minutes, adding that was if she could get him on the naughty step. Sometimes she would have to pull him, kicking and screaming, push and hold him down shouting at him to stay there for the required four minutes. She would restart the four minutes each time he moved or got up. The mother complained she could never get him to say sorry. Eventually she would give up and send him either to his room or out to play.

When the mother was asked to remember what he had done in the previous week to warrant the use of the naughty step she recalled him not wanting to eat what she had made for lunch and on replacing it with his request for tomato soup, he then threw this over her. He had also bitten the dog’s ear and made it bleed and hit his younger sister with a brick. For all three behaviours he was given the four minute treatment. With a smile, she wondered if he would grow up to be just like his dad. She hated it when he laughed at her. When asked who ‘he’ referred to, she replied both – her partner and the child.

Neither mother nor child were ‘in their window’ during the use of the naughty step. The mother did not know of its importance in informing her own parenting skills for her own wellbeing, or how to help her child learn that a level of ‘punishment would fit the crime’ but while his behaviour was unacceptable, he still remained lovable.

Using empathic curiosity

To assess a mother’s ability to change how she interacts with her child, requires the social worker to have a high level of empathic curiosity with little or no blame or shame in tone or words. This is required in order to enable both the mother and the social worker to attempt to understand the mother’s behaviour.

Using empathic curiosity the social worker can engage the mother in conversation to determine the reason(s) for her behaviour. The social worker will need to find out if the mother:

- does not know an appropriate way to behave;

- has the knowledge, but lacks the skills to put this knowledge into practice;

- has both knowledge and skills, but it is her attitude, attachment or emotional issues which underpin or drive her behaviour.

Understanding the mother’s behaviour does not condone or excuse it, but leads to a dialogue through which any potential change can occur or the decision made that change is not possible within an appropriate timescale for her child.

This particular mother (outlined in the case example above) had attended three Triple P courses, had received visits from family support workers and had attended a family centre – on and off – for three years while her children were identified as children in need and then put on child protection plans. Her lack of knowledge and skills were therefore not the issue.

Repeating the resources already tried even with the additional threat of court action or removal of her children would not improve her parenting capacities within any child’s timescale, even if she was willing to undertake her own intensive therapy. Any contact arrangements between this mother and her child while any care proceedings were undertaken would also need to be informed by a trauma model for contact.

See Inform’s guide to A trauma model for planning, assessing and reviewing contact for looked-after children.

To assess a parent’s capacity for change Tony Morrison (1991) suggests the social worker needs to listen, and take note of, the words a parent uses about the problem under discussion.

This helps to determine whether there is an internally driven motivation to change, if change can only be driven by an external motivation or a mixture of both.

For example:

would indicate internally driven motivation.

would suggest external pressure needed whereas,

or

would suggest no motivation to change whatever external pressure was applied.

During the mother’s assessment, the social worker’s use of empathic curiosity focused the mother’s attention on the impact her partner’s violence (now, and during her pregnancy) was having on herself and her baby’s brain development. It also allowed the mother to reflect on her own history of childhood harm, her experiences of attachment and empathy and how the level of terror in the household had, and would, continue to impact on everyone’s ability to attach to each other (Fonagy et al, 2004; Schore, 2003).

They also explored the mother’s feelings of victimisation from other residents in the refuge, her ‘need’ to escape as a result and whether she would consider engaging in therapy if this was offered. When asked about therapy, the mother said she had tried that and had also attended some group work while in the refuge where she learned that she was not responsible for her partner’s violence and therefore it was him who needed anger management, not her (Craven, 2008, 2012; Peace, 2012).

Sadly, the message that it was not her fault did not help her look at her behaviour in her relationship with her son and instead enabled her to blame only her partner for her child’s violence.

Contact

All four components of the trauma model are necessary when assessing contact between a child and the perpetrator. The child’s wish to see the perpetrator, or the victim wanting to continue the relationship, is likely to be complex and not as simple as ‘missing his company’. Remember that where there is a conflict between a child’s, or even an adult’s, innate needs for attachment and safety there will be a disorganised form of attachment or trauma bond (Liotti, 1992).

One of the goals, or result, of giving a child a secure attachment is that this enables the child to separate from the parent in an age-appropriate, positive way (James, 1994; Howe, 2005; Dixon et al, 1992). The child, as it grows to an adult, does not need the parent but wants a continuing relationship with the parent.

One of the consequences of a trauma bond is that separation intensifies the sense of loss which results in acute distress. The child continues to need the parent to meet this unmet need, making separation very difficult if not impossible even though they have experienced significant harm within this relationship.

The adult victim needs the perpetrator. The victim continues to want the perpetrator to meet this need making separation very difficult, if not impossible, despite the evidence that this relationship continues to be harm-filled and dangerous (Herman, 1997; Iminds, 2010).

When the expressed wish to see a parent is explored with a trauma model in mind, children have come up with the following reasons why they have asked for, or agreed to, contact:

- We always have to do what daddy wants or he gets cross.

- Sometimes he gets cross and hits mummy or me for nothing so if I do something, like say I don’t want to go, what will he do?

- I want to see if he has changed like mummy always said he would.

- I can make him be a nice daddy to me and my brother.

- Daddy is fun and gives me things. Mummy is too strict and miserable.

- Daddy says he wants to come home and mummy won’t let him. Poor daddy.

- Me and daddy like doing the things mummy will not do with me.

- It (contact) will happen. Daddy will win this argument as well so if I say yes it will stop the arguments.

- My tummy won’t hurt anymore.

- I miss the dog.

This applies to the behaviour of both the perpetrator and the victim and also leads the social worker to question who appears initially to be the victim and the perpetrator, to determine if the violence within the family is the answer to the problem. If so, which problem? Once this can be determined, the correct interventions, therapies or treatment programmes can be put in place for everyone.

While this phrase provides an explanation for the behaviour, care is needed to ensure the explanation is not used to excuse the behaviour. Too often, assessment and treatment focuses on the answer with little or no short- or long-term effect or change in behaviour or choice of partners.

The connection between domestic abuse and child abuse is clearly made in many studies (Longo, 2012; Prescott, 2005; Ryan and Leversee, 2010). Wolf’s research (2002) on the connection between domestic abuse and sexual abuse of children in the family led him to suggest that an important question to ask victims and children is: how quickly after an episode of violence do the couple have sex?

His research found that if this was happening within 20 minutes of an episode of violence the violence is likely to be a component of the sexual relationship and would therefore be considered a deviant form of arousal. He linked this with Abel and Harlow’s study (2002) which found that perpetrators of sexual violence were not specific in the form of deviant behaviour but were more likely to have more than one paraphilia (also known as sexual perversion or sexual deviation). The question of sexual abuse of the children therefore needed to be considered and questions asked about this as well as the children’s experience of physical harm by one or both parents.

The need to ask about one or both parents was identified in many studies from the 1970s, ’80s and early ’90s. One of the questions asked of the children was whether or not the violent partner was also violent to any of the children. The following table is a summary of research studies where the children were asked as part of the study whether or not their father, accused of being violent with their mother, was also violent to them. Alongside is where the question was also asked of the mother’s violence to the children.

| Research study | Abuse by father to child | Mother to child |

|---|---|---|

| Roy, 1977 | 45% | Not reported |

| Prescott Letko, 1977 | 43% | Not reported |

| Flynn, 1977 | 33% | Not reported |

| Carlson, 1977 | 27% | Not reported |

| Dobash/Dobash, 1979 | 20% | Not reported |

| Okun, 1986 | 44% | Not reported |

| Bowker et al, 1988 | 70% | Not reported |

| Gayford, 1975 | 54% | 37% |

| Walker, 1984 | 54% | 28% |

| Giles-Sims, 1985 | 63% | 55.6% |

| Straus and Gelles, 1990 | 50% | Not reported |

Several studies have also identified increased levels of violence between siblings who are living with parental violence (Holden and Ritchie, 1991; Thornberry, 1994; Wiehe, 1990). This link prompted paediatricians in Hull’s accident and emergency to review and compare whether cases that involved significant physical injury to children, caused by either a sibling or parent, were reported to child protection services. Only those reporting harm by a parent had been reported.

This review led to changes in their referral procedures. As a result of his research on sibling abuse, Finkelhor (Finklehor et al, 2005) invites us to consider the following comment:

If I were to hit my wife, no one would have trouble seeing that as an assault or a criminal act. When a child does the same thing to a sibling, the exact same act will be construed as a squabble, a fight or an altercation.”

It is therefore very important to ask children about violence in their sibling relationships and friendships when they have learned through observation and experience that violence is one, or often the most consistent, way to resolve conflict in relationships.

Using a trauma model to consider the outward expression of anger to hurt and harm as the answer to a problem is useful. Again this does not excuse the behaviour but explains it, which will lead to more appropriate intervention and treatment.

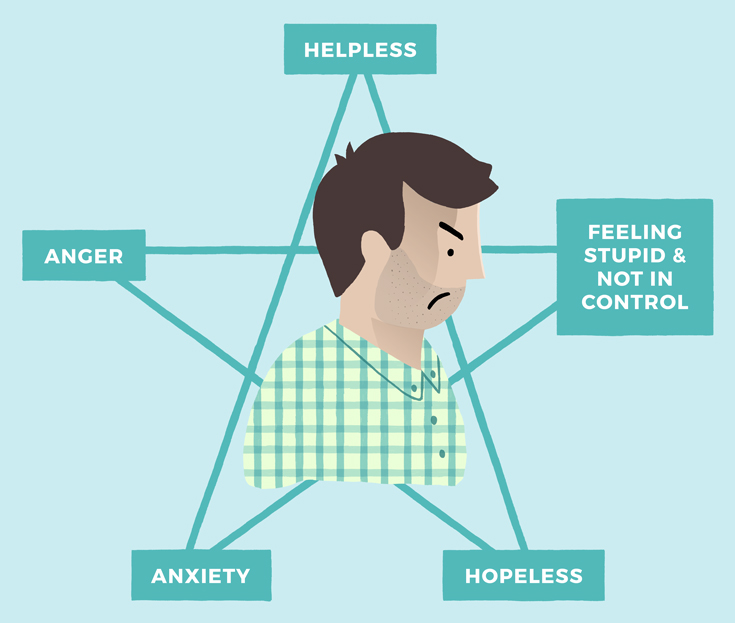

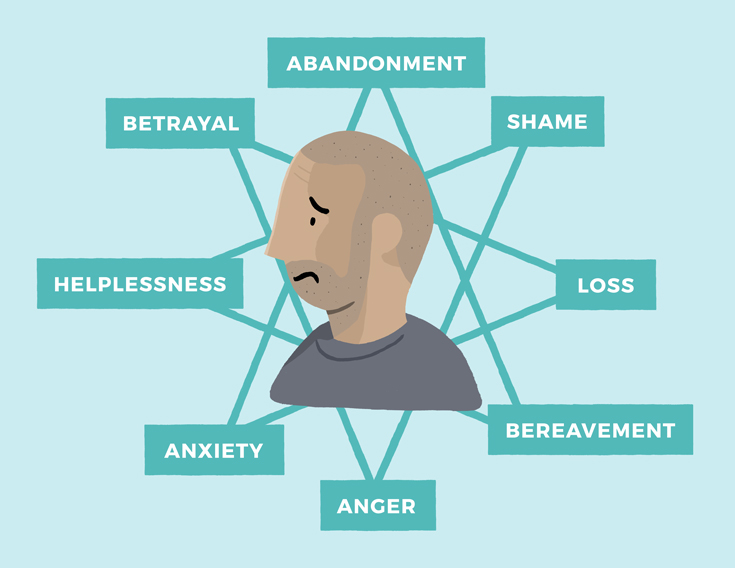

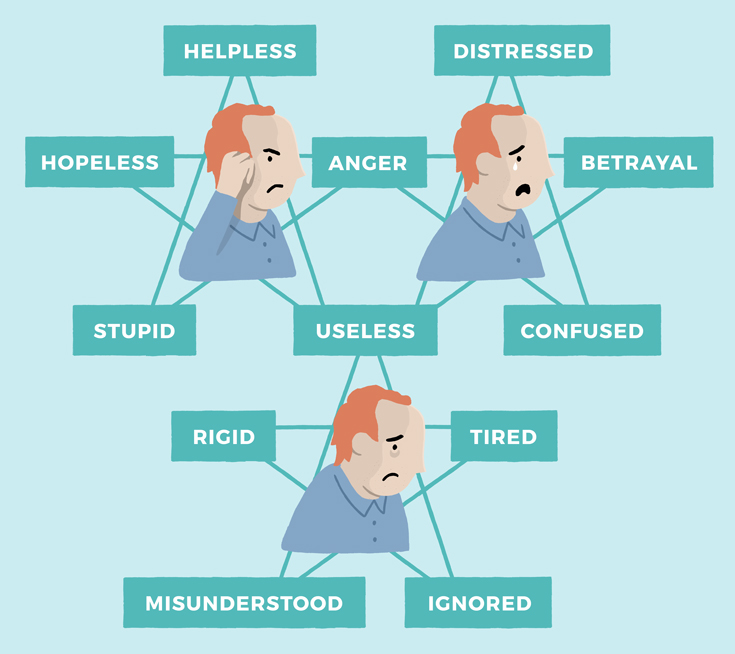

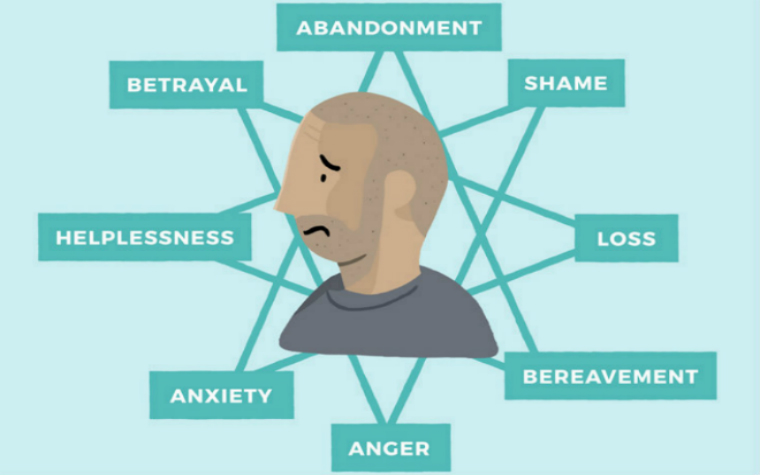

One way to do this is using a five-pointed star to identify the problem that leads to anger. This will enable appropriate interventions with better outcomes.

This is done by the worker drawing a five-pointed star, this is crucial to link the issues on the five points in a way a six-pointed star does not.

It is possible to draw an eight-pointed star.

Or to join several five-pointed stars together where there are more issues identified.

This exercise demonstrates that although a referral is often made because of anger-related problems, anger is in fact a response for not being able to manage the other feelings identified. Teaching skills to manage the other feelings will reduce the need for anger (Longo et al, 2012). Therefore, a referral to an anger management course would not lead to any reduction in anger unless strategies for all the other issues were addressed as well.

It is not uncommon for anger management courses to have a component designed to increase victim empathy. This, however, can be ineffective particularly when the only expression of anger is towards a partner or children.

Teaching this to someone who does not have empathy is likely to increase their ability to use this information to manipulate and shame a partner rather than increase their understanding and concern for the impact their anger has on their partner or children.

Jamie explained this very well when he commented that the information gained about the impact of domestic abuse on victims enabled him to work out how best to tease and torment his partner. Using information about her history, her coping strategies from her history and his ability to attune to her mood and needs, without any modulating empathy, he was able to groom her to meet his predetermined impossible needs and further blame her when she indeed failed to do so. Jamie also used this information to exploit his own history of witnessing his father’s violence towards his mother, and the physical violence he experienced from both his parents, as an excuse for him to feel the way he did. He blamed his partner for not understanding him or meeting his previously unmet needs, winding him up and even for choosing him as a replacement for her father.

Instead of using the jigsaw model to understand his own behaviour, he used this to further shame and blame his partner and her history and by doing so avoided taking any responsibility for it.

Sadly, before being accepted on the anger management course, no assessment had been carried out on Jamie’s capacity for empathy. In the pre-course meeting he used his attunement skills to work out what the social worker wanted him to say and complemented this with what looked like appropriate emotion, regret and a wish to change. As a result, his capacity to be more physically and emotionally dangerous was increased.

This case example emphasises the importance of assessing whether an individual uses attunement, empathy or sentimentality when talking about the impact their behaviour has on others. Understanding the trauma bond between victim and perpetrator, the perpetrator and the children is important when assessing these complex relationships. Children and adults living in a fear-filled environment require high levels of attunement and self-preservation to ensure their emotional and physical survival. It should be noted that using such high levels of attunement reduces or even prevents the development, and use, of empathy.

It is imperative to assess an individual for their capacity for empathy and not just attunement. Attunement can be used by someone to manipulate another into meeting their own needs first. Empathic attunement primarily focuses on the needs of the other and the impact any action may have on the other person.

Another example of the behaviour being the answer to the problem is when the victim behaves in such a way that draws the anger towards her and away from the children. Witnessing harm being done to a loved one is recognised as excruciatingly painful. This is exploited by torturers and kidnappers to ensure the compliance of their victim (Golston, 1992). It is less painful to be hurt oneself than to watch this happen, but then to be praised for doing something which the victim knows was done to protect them leads to feelings of shame and distress and results in the victim feeling not understood which can lead to them withdrawing to avoid these feelings.

The importance of understanding the impact of trauma, and therefore using a trauma model in all aspects of work with victims is crucial in offering appropriate services at all stages of the work – assessment, planning and providing resources. It enables conclusion words such as ‘abused’, ‘traumatised’, ‘resilient’, ‘coping’, ‘reluctant’, ‘intransigent’, ‘nasty’, ‘controlling’ and ‘borderline’ to be explored as coping strategies which were – and still are – needed for survival when living with and recovering from violence. Blaming and shaming does not lead to change: empathic curiosity does.

References

Briere, J (1992) ‘Child abuse trauma’ IVPS Practice Series, Sage, London.

Cairns, K (2002) ‘Attachment, trauma and resilience’ BAAF, London.

Craven, P (2008) Living with the dominator, Freedom publishing

Craven, P (2012) Freedom’s flowers: the effects of domestic abuse on children. Freedom Publishing

Dixon, S.D & Stein, M.T (1992) Encounters and children, paediatric behaviour and development, Mosby, St Louis.

Fonagy, P, Gergely, G, Jurist E.L, & Target, M (2004) ‘Affect regulation, mentalisation and the development of self’ Karnac, London.

Freyd, J (1996) ‘Betrayal trauma’, Haryard, London.

Golston J.C (1992) Comparative abuse: shedding light on ritual abuse through a study of torture methods in political repression, sexual sadism and genocide, Treating Abuse Today Vol 2:6

Herman, J (1997) ‘Trauma and recovery’, Basic, New Hampshire

Howe, D (2005) Child Abuse and neglect: attachment, development and intervention Palgrave Macmillan

Howes N, in Howarth, J, (Ed) (2010), ‘The child’s world’ (2nd Edition), Jessica Kingsley, London.

James, B (1989), ‘Treating traumatised children’, Free Press, New York.

James, B (1994), ‘Handbook for treatment of attachment-trauma problems in children’, Free Press, New York.

Kaufman, J & Zigler, E (1987) Do abused children become abusive parents? American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 57(2):186–192

Kenrick, J (2009), ‘Giving babies stability in care from the start’, Adoption and Fostering, 33, 5-18.

Liotti, G (1992) ‘Disorganised attachment and dissociative experiences: An illustration of the developmental-ethological approach to cognitive therapy’. In H.Rosen & K.T.Kuehlwein (Fds), Cognitive therapy in action. Jossey-Bass. San Francisco, CA.

Lipton, B H (2011) The biology of belief, Hay House, London

Longo R.E, Bays H.L, & Sawyer S, ( 2012) Why did I do it again and how can I stop? NEARI press

Morrison T (1991) Change, control and the legal framework. In Significant Harm ed. Margaret Adcock and Richard White. BAAF, London

Ogden, P, Minton,K, & Pain,C, (2006) ‘Trauma and the body’, Norton, London

Panksepp, J, (1998), Affective Neuroscience, Oxford University Press, New York

Perry, B. D, Pollard R.A, Blakley, T.L, Baker, W.L & Vigilante, D (1996), ‘Childhood Trauma, the Neurobiology of Adaptation & Use-dependent Development of the Brain: How States become Traits’. Journal of Infant Mental Health.

Prescott D.S, and Longo R.E, (ed) Current applications: strategies for working with sexually aggressive youth and sexual behaviour problems, NEARI press

Putnam, F.W (1997) ‘Dissociation in children and adolescents’, Guildford, London

Rich, P, Attachment and sexual offending. Wiley London

Ross, C.A (2000) ‘The trauma model’, Manitou, Richardson TX

Ryan G & Leversee T.F (2010) Juvenile sexual offending: causes, consequences and correction. Wiley

Sapolsky, R.M (2004) ‘Why zebras don’t get ulcers’, Owl Press, New York

Schore, A.N (2003) ‘Affect regulation and disorders of the self’, Norton, London

Siegel, D.J (2012), ‘Pocket Guide to Interpersonal Neurobiology’, Norton, London

Siegel, D.J (1999) ‘The developing mind’, Guildford, London

Silberg, J.L (2013) The child survivor. Healing developmental trauma and dissociation Routledge, London

Steller, M, & Koehnken, G (1989) Criteria-based statement analysis. In D. C. Raskin, (Ed.), Psychological Methods in Criminal Investigation and Evidence, New York

Swaab, D (2014) We are our brains: from the womb to Alzheimer’s, Penguin

Terr, L (1997) ‘Too scared to cry: psychic trauma in childhood’, Basic Books

Van der Kolk, B, McFarlane A.C, Weisaeth, L eds (1996), ‘Traumatic Stress’, Guildford Press New York

Wieland, S (2011) Dissociation in traumatized children and adolescents, Theory and clinical interventions. Routledge, New York

Wilson, J.P & Lindy, J.D (1994) ‘Countertransference in the treatment of PTSD’, Guildford, London.